By Guneet Kaur and Abhimanyu Nag

Recall getting those late night messages from your favourite bank about “technical difficulties” and “payment disruptions”. The subject line is somewhere along the lines of “URGENT: Service Alert - [Bank Name] is experiencing technical difficulties” and you, like most people, go about your day with no worries and thoughts. However, it is important to understand the incentives behind selective disclosure and “obfuscation” of the problems which in reality may have had caused panic withdrawals and liquidity crises. This blog post is a short code demonstration about manipulated signals given to different market participants by a bank in order to minimize their probability of ruin (i.e liquidity becomes HQLA buffer) and therefore risk insolvency.

Liquidity Disclosure During a Payments Disruption

On an ordinary trading day, a large Schedule I bank is processing tens of billions of dollars through high value payment rails. Corporate payrolls, securities settlements, interbank obligations, and treasury flows are moving continuously, supported by a finite intraday liquidity buffer (say HQLA buffer for eg) and carefully calibrated payment queues. Treasury and operations teams monitor this system in real time through internal dashboards that track queue lengths, liquidity usage, and incoming versus outgoing flows.

Mid morning, something routine but uncomfortable happens. Assume a non catastrophic operational issue slows the release of payments. Queues begin to lengthen. Some large value transactions are delayed by thirty to sixty minutes. There is no solvency concern, no capital impairment, and no regulatory breach. The bank remains fundamentally sound. Events like this occur several times a year across the system and are usually resolved quietly.

What matters, however, is not the disruption itself, but how it is communicated.

At approximately 10:15 a.m., operations faces a disclosure decision. Information must be shared (both for operational coordination and client confidence) but the precision and timing of that information are not innocuous. They shape beliefs, incentives, and ultimately behavior across the payment network.

Under a high precision, real time disclosure approach, the message is explicit: payment queues are elevated, average delays are approximately forty‑seven minutes, and intraday liquidity usage has reached eighty‑two percent of the available buffer. This information is shared with major counterparties, visible to large corporate treasury clients, and partially inferred by markets through settlement timing and informal communication channels.

Alternatively, the bank can choose a coarse, lagged disclosure. The message is simpler: some payments may experience delays, and updates will follow later in the day. No queue metrics are published. No liquidity usage numbers are disclosed. The communication remains compliant and accurate, but deliberately imprecise, with status updates every two to three hours rather than continuously.

Both approaches are defensible. Both reflect real practices within Canadian banks. But they are not equivalent.

High precision disclosure reduces uncertainty for any single counterparty, yet it also synchronizes beliefs across the network. Large counterparties, seeing the same numbers at the same time, may rationally choose to delay outgoing payments to conserve their own intraday liquidity. What begins as a benign operational delay can, through coordinated behavior, evolve into a liquidity drain.

Coarser disclosure does the opposite. It increases individual uncertainty while reducing collective coordination. Payment behavior becomes staggered rather than synchronized, buying the bank time to absorb the shock internally and restore normal flows.

Simulations

To make the disclosure–liquidity trade‑off concrete, we construct a minimal intraday liquidity simulator that captures three elements simultaneously:

- Payment‑flow dynamics (inflows vs. outflows),

- Asymmetric information disclosure to different market participants,

- Endogenous behavior that feeds back into liquidity and can trigger ruin.

The goal of these simulations is not to forecast any specific bank’s balance sheet, but to isolate a mechanism: how the precision and timing of information disclosure can convert a routine operational disruption into a liquidity crisis, even when fundamentals remain sound.

Intraday Liquidity Model

In keeping as close to real world conditions as possible, we model a single state variable:

This represents cash and immediately monetizable high‑quality liquid assets (HQLA) available to meet payment obligations.

We initialize the system as follows:

Crossing corresponds to functional ruin i.e forced liquidity actions, gridlock in the payments system, or emergency funding usage.

We simulate

intraday time steps (interpretable as settlement

intervals or minutes).

A payments disruption begins at

and lasts for

time steps.

During this window: - incoming payments are throttled, - outgoing obligations continue largely uninterrupted, - information‑driven coordination risk becomes material.

Assume liquidity evolves according to the following formula:

Under normal conditions, inflows and outflows are balanced on average and can be modelled by sampling using a normal distribution:

inflow = np.random.normal(0.35, 0.08)

outflow = np.random.normal(0.35, 0.08)During the disruption period:

- Inflows are throttled to 35% of normal throughput, reflecting delayed or queued incoming payments.

- Outflows increase modestly due to contractual obligations and payment catch‑up dynamics.

This setup represents operational gridlock, not a balance‑sheet shock.

Now we model two representative belief holders who receive different signals about the bank’s intraday liquidity.

Majority shareholders and sophisticated counterparties observe near‑real‑time liquidity with minimal noise and update beliefs rapidly. This can be represented as:

S_ms = L + np.random.normal(0, 0.10)The belief updating follows an exponential smoothing process:

Ths comes from an intuitive judgement of parameters. Future idea would be to get it closer to the real market belief updating process.

The general public receives processed and potentially distorted information (as “some problem” instead of the exact specifics). Belief updating is slower:

The actions of both types of parties depend on perceived liquidity, not actual liquidity.

def shareholder_outflow(Lhat):

return max(0, 0.20 * (7.5 - Lhat))

def public_withdrawals(Lhat):

return max(0, 0.35 * (8.0 - Lhat))As beliefs deteriorate: shareholders hedge, pull funding, or demand collateral, the public migrates deposits or delays payments. These behaviors directly drain liquidity and feed back into future states.

Disclosure Regimes

All simulations hold fundamentals fixed and vary only the public signal .

Regime A - High‑Precision, Real‑Time Disclosure

S_gp = L + np.random.normal(0, 0.12)Regime B1 - Bucketed and Noisy Disclosure

if L > 9.0:

base = 9.5

elif L > 6.0:

base = 7.5

else:

base = 5.0

S_gp = base + np.random.normal(0, sigma)Regime B2 - Precise but Lagged Disclosure

S_gp = L[t-k] + noiseRegime B3 - State‑Dependent Obfuscation

sigma = 0.20 if L >= 7.0 else 0.80

S_gp = L + np.random.normal(0, sigma)Core Simulation Loop

Finally, we talk about the core simulation loop. It advances the system forward one intraday step at a time. At each step, the model first determines whether the bank is operating under normal conditions or within the payments disruption window. This matters because disruptions selectively impair inflows while leaving most outflows intact, creating a timing imbalance in liquidity.

Next, baseline payment inflows and outflows are realized. During a disruption, inflows are throttled and outflows are slightly amplified, capturing operational gridlock rather than any deterioration in balance‑sheet quality. These flows determine the mechanical evolution of liquidity.

Information then enters the system. Majority shareholders and sophisticated counterparties observe a near‑real‑time signal of liquidity, while the general public receives a noisier or coarser signal depending on the disclosure regime. Both groups update their beliefs using exponential smoothing, meaning recent information matters more, but past beliefs still anchor expectations.

Behavioral responses follow from these beliefs. If perceived liquidity falls below group‑specific thresholds, agents defensively withdraw funding, delay payments, or demand collateral. These actions create endogenous outflows that directly drain liquidity.

Finally, the bank may take internal liquidity actions such as converting HQLA into cash to partially offset stress. Liquidity is then updated, and the process repeats. If liquidity falls below the critical threshold, the simulation stops, marking a functional liquidity failure.

for t in range(T):

crisis_flag = (t_crisis <= t < t_crisis + crisis_duration)

inflow = np.random.normal(0.35, 0.08)

outflow = np.random.normal(0.35, 0.08)

if crisis_flag:

inflow *= 0.35

outflow *= 1.15

S_ms = signal_ms(L)

S_gp = signal_gp(L, crisis_flag)

Lhat_ms = alpha_ms * S_ms + (1 - alpha_ms) * Lhat_ms

Lhat_gp = alpha_gp * S_gp + (1 - alpha_gp) * Lhat_gp

run_out = shareholder_outflow(Lhat_ms) + public_withdrawals(Lhat_gp)

action = liquidity_actions(L, crisis_flag)

L = max(0, L + inflow - outflow - run_out + action)

if L < L_critical:

breakResults

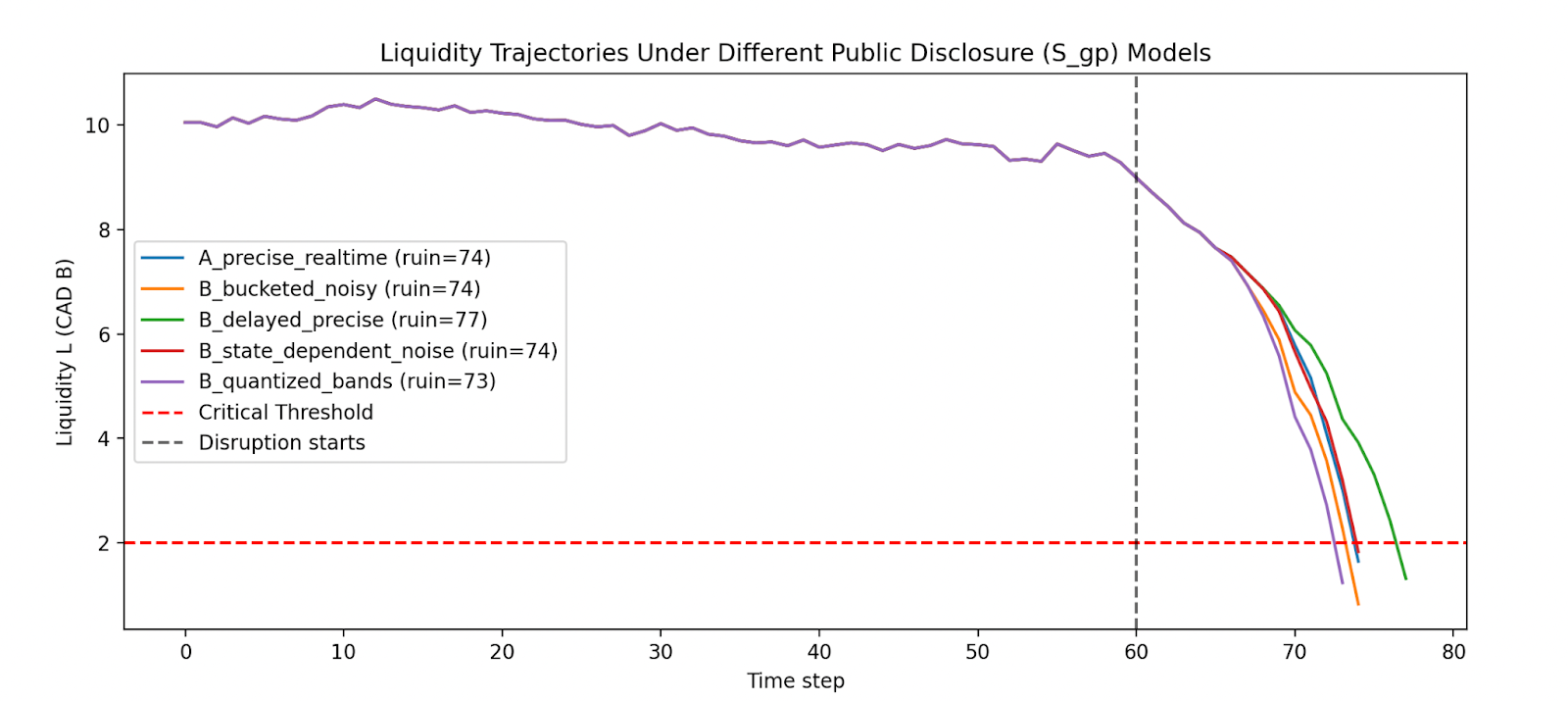

Running the same simulation under different disclosure regimes produces materially different liquidity trajectories, despite identical fundamentals.

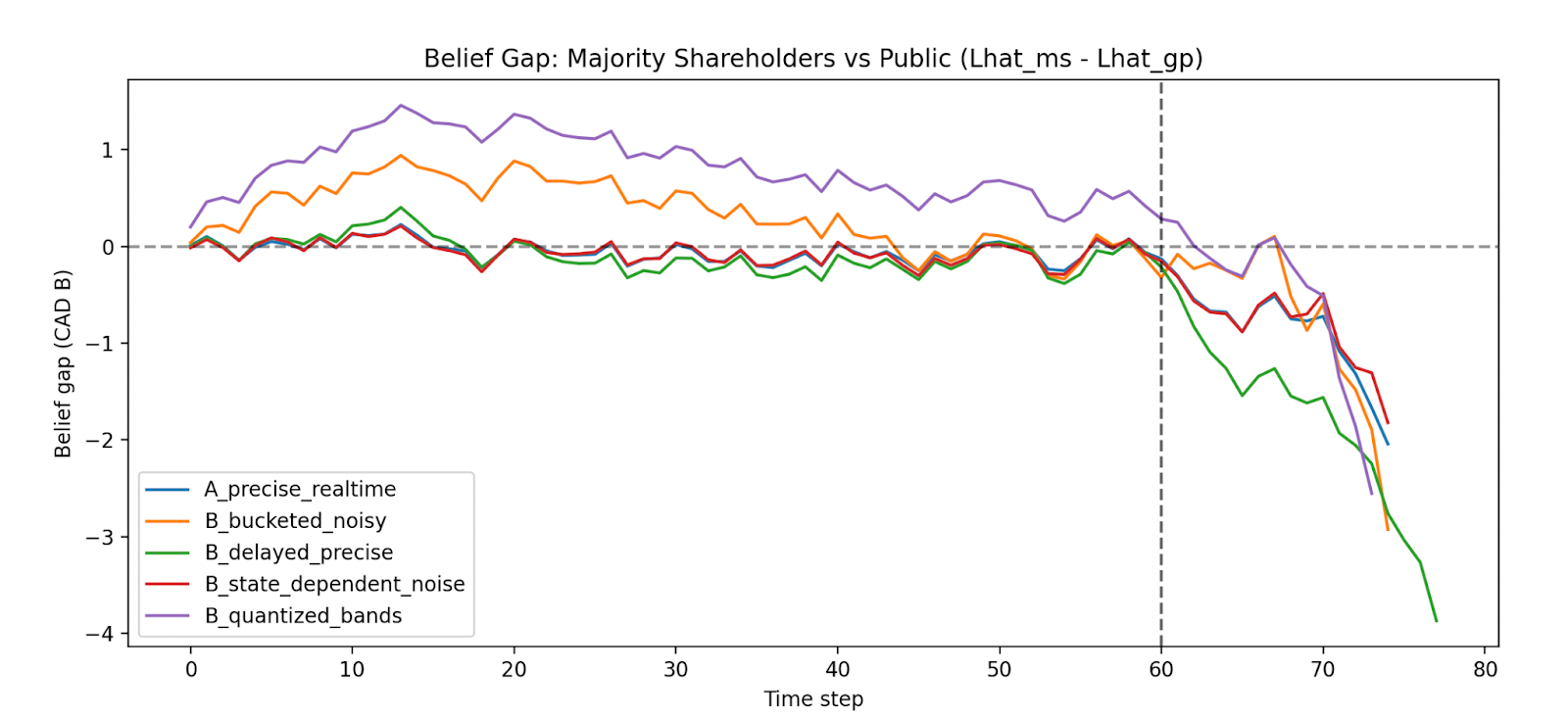

Belief Gap Mechanism and Interpretation

A useful diagnostic is the belief gap:

High‑precision disclosure collapses this gap rapidly. Obfuscation preserves belief dispersion.

Ruin tends to occur when belief dispersion collapses faster than liquidity can adjust.

These simulations highlight a critical insight:

Liquidity crises are not driven solely by balance‑sheet fundamentals, but by how those fundamentals are revealed.

- High‑precision, real‑time disclosure leads to earlier and sharper liquidity drawdowns as beliefs synchronize.

- Bucketed or delayed disclosure often delays or avoids ruin by weakening coordination.

- Quantized disclosure introduces cliff effects, where liquidity remains stable until a reporting threshold is crossed, triggering abrupt behavioral shifts.

Conclusion

In modern payment systems, information is not just descriptive. It shapes expectations, coordinates behavior, and under stress, can move liquidity just as powerfully as balance‑sheet fundamentals. Banks deal with operational disruptions all the time, including delayed payments, growing queues, and temporary system slowdowns. Most of the time, nothing is actually wrong. But these are exactly the moments when liquidity stress can emerge, not because the bank is weak, but because everyone starts believing the same thing at the same time.

This project was built to understand that dynamic. We were not asking whether transparency is good or bad, but how the way information is released changes outcomes. By keeping fundamentals fixed and only changing how liquidity information is disclosed, the simulations show a clear pattern. Highly precise, real‑time disclosure reduces uncertainty for individual participants, but it also aligns beliefs across the network. That alignment encourages coordinated defensive behavior, which can quickly drain liquidity. Coarser, noisier, or delayed disclosure does the opposite. It keeps beliefs dispersed, slows coordination, and gives the bank time to resolve operational issues internally.

The takeaway is not that banks should hide information. It is that information itself is a risk management tool. Banks already think carefully about capital buffers, liquidity ratios, and stress scenarios. This work suggests that disclosure policy, meaning what is said, when it is said, and to whom, deserves the same level of care. Disclosure is not binary. It is a lever, and in stressed conditions, pulling that lever too hard can create the very crisis it was meant to prevent.

This blog was jointly written by the two authors. Thanks for reading and reach out with questions, suggestions or improvements to Guneet Kaur or Abhimanyu Nag!